The Eolder’s Ramblings

Myles Stevens

Next year is Regia’s 40th birthday hence Regia XL. I’m keen for it to be the type of year where we look forwards and do new things. Yes, look at cool things we’ve created and done in the past, but we build on that to create new memories that make people who missed out seethe with jealousy.

Should we camp near a river a short row from a convenient pub and spend our days rowing people back and forth?

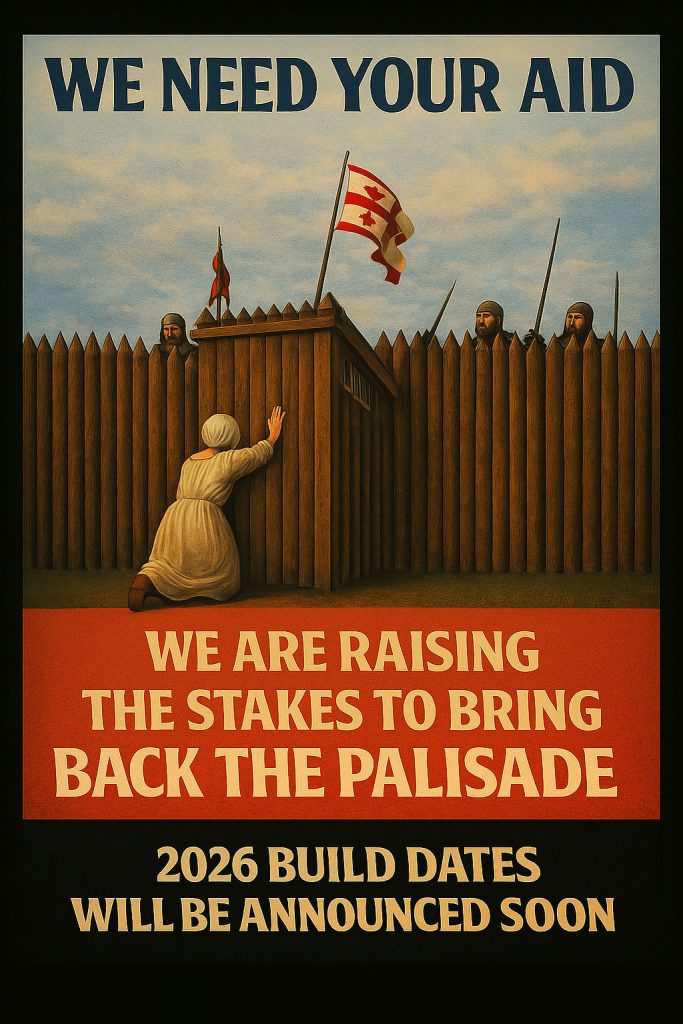

Should we build a palisade bigger and better than our old one so that we can assault it with rams and ladders?

Should we make Sherwood even better? Maybe as a crazy Norman tourney with teams from the cultures we represent battling, riding and shooting whilst the rest of Regia cheer from the sidelines?

If you like these ideas and want to make them happen, speak to the officers: let’s make it all a reality.

We already know that Wychurst at war is going to be more immersive and magical than last year’s brilliant event. I’m still hoping the organisers want my particular talents. I can do every emotion as long as it’s angry and deliver a nuanced performance as long as it’s shouty you want.

We also have a truly special weekend planned for Leominster priory: a Viking boat burial and camping in an actual church yard!

So, If you’ve got ideas of your own on how we should celebrate Regia XL, get in touch. I think next year is going to be one of Regia’s best ever seasons.

A Year In Regia

A summary of our National Shows from our members

Event Highlight: Kingston-Upon-Thames

Samuel Clarkbourne

Sometimes things come around at exactly the right time.

The first eight months of this year were tough. I had spent my mental energy on a job that was not right for me, and by July my outlook was glum. I knew I would be leaving to go back to my old role, and despite that turning out to be an excellent turn of fate it was hard to see the positives in the moment.

When I was asked to play Æthelstan at Kingston I was unsure what to think. Regia had been a welcome reprieve from work, but I had only been to local shows so far that year and felt a little bit disconnected from the national scene.

It was therefore hard not to be overjoyed (or overwhelmed!) by what occurred. After some very fun training I was paraded through the streets in a gorgeous dalmatic, with two horsemen at my back and a line of warriors and retainers shouting:

‘VIVAT ÆTHELSTAN, REX ANGLORUM!’

The crowds pressed in on either side as I tried to hold onto a stoic expression that one would expect from a medieval king. The coronation dalmatic was made by Catherine Stallybrass who used handwoven wild silk with Byzantine silk which was based on finds from Oseberg. They might just be the daftest lions you have ever seen!

Thereafter I was led to a throne, where our impeccably dressed Ecclesiastical team had arranged a coronation based on an abridged Second Ordo. I was asked to respond to an admonition with a promise to the Church, which read as follows:

‘I promise to you and grant that I will preserve for each of you and for the churches entrusted to you, canonical privilege and due law and justice, and that I will maintain protection as much as I am able with the Lord’s assistance, just as a king should in his kingdom rightly maintain protection for each bishop and for the church entrusted to him.’

Afterwards I had to prostrate myself before the throne, where ‘Te Deum Laudamus’ was sung and an invocation made by the bishops. I was then anointed with oil and presented with the ring, sword, crown, sceptre, and rod (in that order). Once King I was greeted by the Mayor of Kingston who delivered a speech to and about me, before parading once again. This time I returned to our camp to take pictures with members and the public and have a much earned rest on my new throne.

“Out of body” is how I would describe the experience, and it was exactly what I needed. All ill-thoughts of that year floated away and I felt for once quite positive about something. When I returned to work for the last two weeks I had not a care in the world.

I am so grateful for the experience. Many, many thanks go to all those who arranged it. Special mention goes to Wilfrid and his Ecclesiastical team, to Russell and the Haestingas for getting us in the door with the event the previous year, and to Greg for both lending me his silk scarf (to cover a tattoo!) and for being a wonderful Æthelstan on Sunday.

Now that I am General Secretary I hope to give back to such a wonderful society that, without knowing, helped me exactly when I needed it.

To read more of Samuel’s Early medieval posts, please visit his blog page: Mīn Webblēaf

Wychurst

Jane Bateman

Another year has passed in the blink of an eye with much occurring at Wychurst. The 12th night feast of 2025 was a culinary delight and the evening even brought a dusting of snow. My birthday in February and I brought my own huge Rice Krispie cake to celebrate.

The cottage battened, shingled, wattled and partially daubed. The old rotten gatehouse removed and replaced. Some fun training in joint construction. The longhall has had a spruce up (work in progress) but loving the colours, which oddly are the colours of my living room and bedroom!

The chilled Wychurst weekend and very quiet craft and graft and of course, more cake. Tebay oaty biscuits have become a favourite at Wychurst and at home! I’ve missed out lots but come and see for yourselves or follow what’s happening on the Wychurst Facebook page.

Officer Elections

General Secretary:

Samuel Clarkbourne

Chairman of the High Witan:

Adrian Pinn

Military Training Officer:

Rob Howell

Living History Exhibit Coordinator:

Helen Mallalieu

Master-at-Arms:

Ian Morgan

Communications Officer:

Malcolm Butler

Merchandising Officer:

Toby Dones

The full list of Officers is on our website: Who’s Who

2026 Events

Twelfth Night

3rd Jan, Wychurst

Islip

17th-18th Jan, Oxfordshire

Jorvik Viking Festival

21st Feb, York

Wychurst at War

25th-26th Apr, Kent

Leominster Priory

30th-31st May, Herefordshire

History in the Park

5th-7th Jun, Fife

To help make our 40th birthday year even bigger and better we want to bring back the palisade. This dynamic part of our shows was a firm favourite amongst members several years ago, making a fantastic backdrop and dramatic battlefield. We would like to use it this year and beyond at events like Detling and Sherwood. But we need your help to bring it back. Skilled and unskilled members are all encouraged to help out. Dates will be announced very soon. Please speak to Matt Town if you are interested.

Keep up to date with all our upcoming events: Diary

Merchandise

We have lots of merchandise designs which can be found on: Regia Anglorum Shop

Myles’ designs are available at: Regia Anglorum Store

Regia Archives

Alongside the historical issues of Clamavi, some old Regia documents have been added to the Archive page for you to browse.

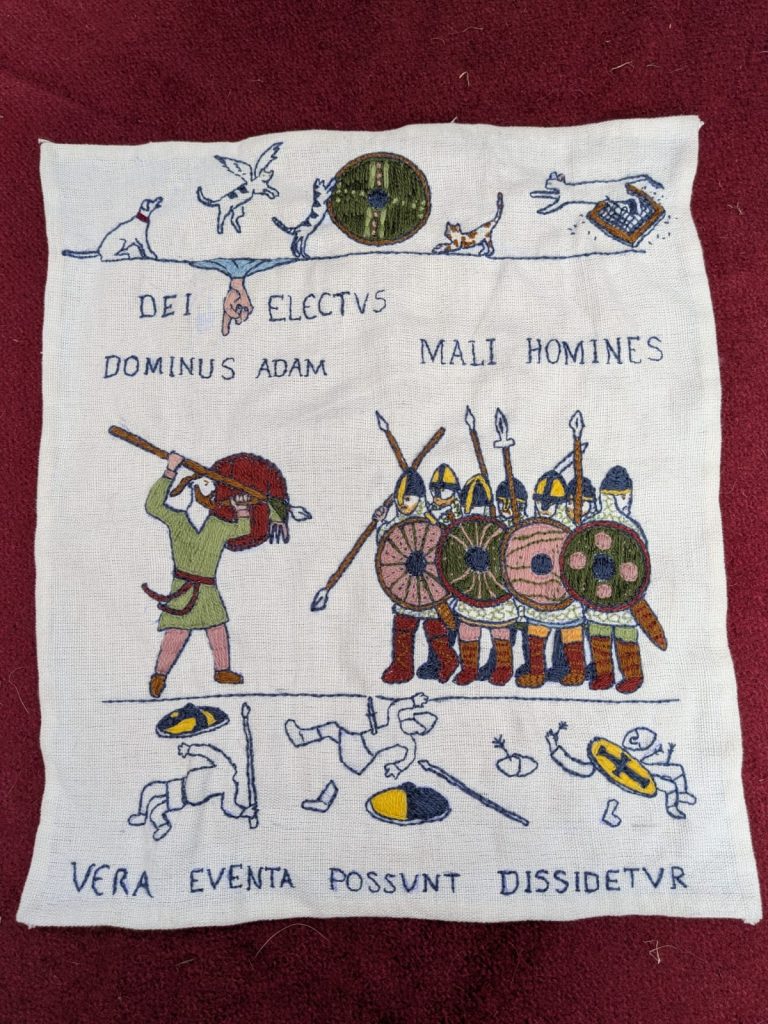

Throwback

This years rallying throwback is to the tenth issue of Clamavi.

Please note any opinions expressed in this item are solely that of the author and does not reflect the views of the current editor.

Online groups

Here are some great places to find out society information or hang out with members with similar interests:

A summary of this year from our Officers

Military

Tom Robinson

After seven incredible years, I am not re-standing as MTO and the role now passes to Rob Howell. What a journey it’s been! Officerships can be more work than expected, but this role has truly been one of the most rewarding things I’ve done.

This year brought some real highlights. Wychurst at War was a standout success, thanks to its immersive, story-driven approach. Your feedback has been fantastic, and we plan to build on this format for future events—so watch this space! We also made progress toward introducing show fight testing into training and this is ready for Rob to implement in the new season.

I’ve always believed Regia’s battlefield culture is something special. The positivity, humour, and teamwork you bring—rain or shine—make every event a joy. Leading you onto the field as one society has been among my proudest moments. A heartfelt thank you to everyone who makes this hobby possible, especially the training team past and present. Their ideas and commitment have been the backbone of everything that’s gone well. I’m excited to see where you take the battlefield next—here’s to the future!

Living History

Helen Mallalieu

Another season has come to a close, and it’s been a busy one—back to pre-COVID levels of national shows! While I only managed to attend a few events personally, those I did were fantastic, and I want to thank my deputies for stepping up, especially at Wirral when car troubles meant they ran the LHE all weekend. The LHE continues to go from strength to strength, with a huge variety of displays across the season. Highlights included York’s return, Craigtoun’s brilliant multi-period show, and Sherwood—the largest event of the year with 190 members and 80 structures. At Sherwood, we trialled a new idea: a Saturday morning meeting with representatives from each wic to discuss authenticity and LHE. It worked well, and we plan to make this a regular feature, with each wic nominating a weekend contact.

Please keep safety front of mind at our events. This year fires were left unattended at Sherwood and an unguarded weapon was picked up by the public at Hastings. These incidents could have had severe consequences. Fires must never be left unattended or in the care of children, and both fires and weapons must always be behind a barrier.

Thank you all for making this season such a success—here’s to an even better year ahead!

Maritime

Greg Collier-Jones

Def. Wooden Boat: a timber lined hole in the water into which you pour time and money to no discernible effect.

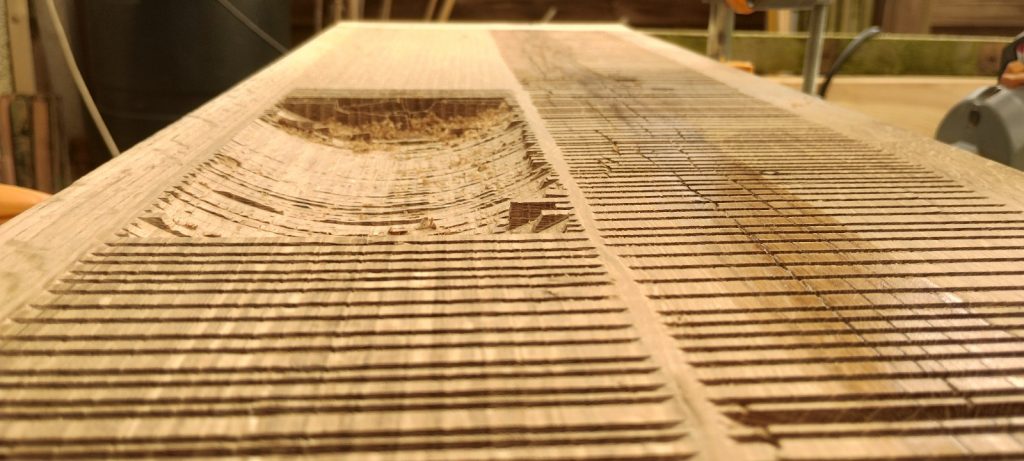

That has somewhat echoed through the last year. I thought rather than précis my officers report I would give a more full description of what exactly went wrong with the Bear and how it was fixed. I will try to keep it understandable.

On the first of our winter maintenance weekends some bolt holes, we believe from the original construction, joining two parts of the keel (backbone) were found to be retaining water and some softness was discovered. Great, we will cut it back, stick some rot hardener on it, fill it and cap it. That is a job for the next work weekend.

The next work weekend rolls around and it’s filled up with water again. So everything gets dried out, again. I think this is where we bought cat litter to soak it up over night. The next day more digging with a chisel reveals around 40cm of rotten wood. We are fortunate in the way the boat is constructed. While the keel should be one bit of oak in a T-section, it is actually in two parts; a l with a – bolted to the top. And the rot has only affected the –. This is still a vital structural part but it is not in the true keel. Now with something like this we cannot just cut it square and be done with. Any repair needs to be long scarfed in (a diagonal join at about 20 degrees off the horizontal). This means the removal of healthy wood up to 1.5m to give us material to bolt onto. It is also in the bottom of the boat, crossed with structural supports, and can only be done with hand tools. This work took a full weekend of Tom Gibson’s time working with chisels to cut back the needed material.

After an intermittent period of purchasing wood and fasteners (bolts for you and I, but fasteners, if you sell them, thanks Joe Bhart) we return for weekend 4, or is it 5? Between myself, Tom and Joe we cut and shape the new keel hog. Thanks to Patrick O’Connell for the loan of his workshop and planer thicknessers. By the end of Saturday we have done a test fit. These things cannot be rushed, so Tom keeps telling me. It is then just a case of fitting all the bolts, sorry fasteners, and she is ready for the Wirral Viking festival …err… the next weekend.

Why have I told you this long and rather dull story about bits of wood A1 grade fasteners? Not sure, I just thought you might want to know what has gone on this year… mostly this.

Missiles

Tony Peel

It’s been another busy year for the missile team, with arrows and javelins flying across almost every national battlefield. Javelin sessions remain popular—especially since moving them to the end of the day. Archery ranges have been well attended, and intensive sessions are proving popular even for those not planning to do combat archery.

Combat archery has grown noticeably, archers are making a real impact on the battlefield, supporting pushes and countering threats. Crossbows are also appearing—five members own them, and two have used them in combat—but they remain less versatile than bows and may face legal complications.

Missile regulations were updated this year to include crossbows, which five members now own with two having used them in combat. We also have a new javelin ruling which prohibits combining javelins with two-handed spears for safety. Arrow attrition has dropped despite heavier use, though Wychurst at War gate fights still take their toll!

Equestrian

Claire Collier-Jones

This year brought two fantastic equestrian events and plenty of memorable moments. Whilst we were not able to put on our own equestrian show at Kingston due to horse hire and rider diary clashes, we hired in Alan and Rosie from The Troop, who wowed crowds with parades, skill-at-arms displays, and even a cavalry-infantry session—great for both horses and warriors. Watching them in action was inspiring, and I’ve picked up plenty of ideas for the future!

Sherwood was another highlight, with six horses and riders creating a stunning spectacle. Our new rider, Robyn, impressed us in the skill-at-arms displays, and the battlefield gave us one of my favourite moments—a cheeky exchange between Stuart (riding Ben the horse) and Ben (the warrior) who offered his apple to the horse mid negotiations! I’m exploring wireless microphones so audiences can enjoy these gems too. We also trialled a cavalry-infantry scenario, which proved so popular we’ll plan for bigger numbers next time.

Easter’s training weekend at Welsh Horse HQ saw riders sharpening their skills and shaking up the leaderboard in a friendly competition. Looking ahead, we’re planning more training weekends—including a potential one in the northeast—and hoping for another Sherwood event. Some of our riders returned to Hastings this year, joining Nigel Amos’ Conroi, a testament to their hard work and high standards of kit and horsemanship. Here’s to more equestrian adventures in the year ahead!

Ecclesiastical

Wilfrid Somogyi

This year has been a busy one for the ecclesiastical team! We began with an overdue update to the ecclesiastical regulations—already circulated to members—which serves as a stop-gap while work continues on a full supplement to the authenticity guide. In the meantime, GLs with members considering monastic or other ecclesiastical portrayals should pay close attention to the new rulings on hoods and belts and seek advice from the team.

Event highlights included the wedding of Malcolm III and Margaret at History in the Park, followed by the coronation of Æthelstan at Kingston upon Thames—complete with three bishops! Huge thanks to Andy for lending his crown and John for supplying the sceptre. At Detling, the team pulled together at short notice to deliver an oath-swearing ceremony and funeral, and at Wychurst at War we added drama with one dead monk and a treacherous abbot. Our new ecclesiastical tent has been a hit at national events, earning great feedback from members and the public alike.

MaA

Simon Kent

As the 2025 show season wraps up, it’s time to reflect on another successful year. First, a huge thank you to the hardworking MaA team and all those who stepped in to help—Regia thrives because of your time and energy.

On the battlefield, things have run smoothly, with only the usual late-season challenges like tired shields and Sunday rust creeping in. Please keep up regular maintenance to avoid last-minute fixes! This year saw a slight change to the muster process: combatants must now pass the AO team before MaA checks. It’s working well overall, but remember both steps are essential for safety. We’ve also nailed the “use the designated gate” rule—great job everyone! One small gripe: disposable cups have been withdrawn after repeated litter issues, so please bring your own drinking vessel to future shows.

In terms of regulations, the big news is the introduction of 6mm shields following a successful trial—check the appendix before making one. Media protocols have also tightened, so photographers should review the updated guidelines to avoid any awkward moments.

Thanks for making 2025 another fantastic year. You are now all in the safe hands of Ian Morgan who takes over the role for the season ahead. If you have ideas for improvement, he would love to hear them.

Wychurst

Wychurst Project Council

Wychurst has been buzzing with activity this year as we continue to strengthen and expand our beloved burgh. After a brief summer pause for the reenactment season, work resumed in earnest, and the results are impressive. The new gate tower is well underway—the main structure stands proud, and we’re now preparing the base and roof to complete it by year’s end. Alongside this, a new access bridge near the cookhouse has transformed the site, making it easier to navigate and adding a brilliant spot for training and skirmishes. It’s practical and fun—a win-win!

As winter draws in, our focus shifts to giving the hall some much-needed care. Fresh paint, repairs to frost-damaged lime panels, and roof maintenance are all on the agenda, with scaffolding in place to make the job safe and efficient. Huge thanks go to our maintenance crew, whose hard work has freed us to tackle these bigger projects and dream even bigger for the future (yes, there’s talk of a church!).

Beyond the building, our events have been just as lively. 12th Night was a feast to remember—thanks to Darren and his team for the incredible food and to Wilfrid for top-notch entertainment. The Regia Festival may have been smaller this year, but it was wonderfully relaxed and gave us time to dive into living history. We even managed to daub a cottage wall—messy, smelly, and utterly satisfying! Plus, the bread oven from last year’s project is now baking beautifully. With filming ventures and LARP groups joining us, the site has never felt more alive.

Finally, a nod to Wilfrid, our Wattle & Daub Coordinator, and the exciting coppicing project now underway. Hazel trees are being managed, and thanks to the Woodland Trust, new saplings will soon line the northern border, setting us up for sustainable building for years to come. To everyone who lent a hand this year—whether for a few hours or many—you’ve helped keep Wychurst thriving. Here’s to another year of building, feasting, and making history together!

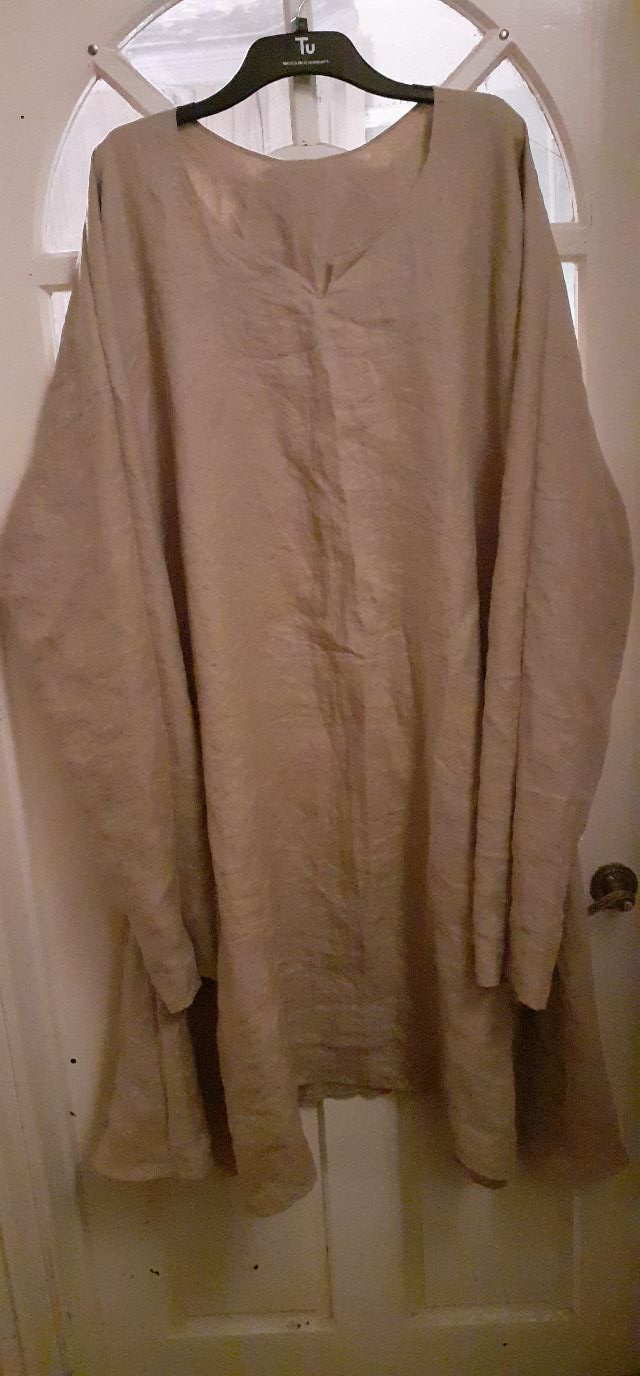

Regia Makes

Regia is full of talented folk. Here are just a few projects from the last year to inspire you.

My Ridiculous Crafting Journey

Adam Moss, Head Senior Master Wizard Chief Crafting Consultant Officer Coach for Saltwic

I hate crafting. I love crafting. I’m obsessed with crafting. I craft for a purpose. I craft for enjoyment.

These are, one and all, true.

Soft kit

All the bags!

Jessica’s hood

…My embroidery list looks at me… I look at my list.. we both know what happens next.. a new craft is looming…

What have YOU, Reader, got to show me that I can obsess over?

A jack of all trades, but Mastermyr of none…

Ben Rees-Roberts

After being in the hobby a few years now, I have acquired a fair amount of kit, including wargear, and LHE knickknacks! Being the disorganised person I am, I kept strewing said kit about the house, and then panicking trying to find it to bring it to events! I resolved, therefore, to put it all in one place. After having a bit of a chin scratch, I decided that the only logical decision would be to build my own, authentic kit and weapons chest! After a bit of research, the Mastermyr tool chest looked cool, and more importantly, was achievable! I was particularly taken with this chest as it had a robust, integrated locking mechanism, meaning valuables could be safely stored on the wic!

This chest is slightly longer than the original, to allow swords and axes to be stored in it. The wood is 20mm oak, with the lid being a 45mm thick slab, which was shaped and hollowed out on the inside face to reduce weight. Like the original, it has angled sides, meaning it is bigger at the bottom than the top!

I was really pleased with how this project came out, and it has been a very useful addition to our Wic! It event acts as a handy, extra seat, as well as a nifty storage solution! A huge thank you to my father-in-law for his help with this project!

NOT THE BEARD! He bellowed.

Fed up with lungs full of smoke, and my luscious locks, and somewhat straggly beard (despite which, I am very attached to) being singed, crisped, and straight up burned, whilst tending to the fire, I decided to invest in a set of bellows! Cue hours of searching for a set to buy … but there were none to speak of. FINE! I’ll do it myself…. But where to start? Where any good project starts, of course! By bombarding those who know with questions, crazy plans, and silly ideas! I would like to take this opportunity to apologise to, and thank, Ted and Roland for their guidance and patience!

The bellows themselves are made from 20mm ash planks, braced at the widest point. The intake valve is a 32mm hole in the bottom board, which has a one way, wooden flap that closes with a satisfying click with every puff of air! Following advice, I created grooves along the top and side faces of the boards, where the leather is sewn on, to allow a better seal, and to reduce the wear and tear on the thread. I used 3mm leather for the ‘bag’ which I soaked in neatsfoot oil, to keep it supple.

The main issue was that exit hole for the air was too large, creating more of a ‘puff’ of air, rather than a nice steady stream. This was solved with the addition of an antler nozzle (courtesy of Roland, cheers dude!) which reduced the diameter of the hole, making the bellows far more effective.

New Groups

Cantwaraburh

Katya Zielonko

Cantwaraburh is one of Regia’s newest groups. This group was formed out of a want of more authenticity throughout the day and into the evenings at reenactment events. Our members are wanting to provide a space of investigation, research and experiencing reenactment outside of wimples on.

Our land grant is the medieval city of Canterbury, and because of this we want to represent the Anglo-Saxon culture of this important city in Kent. Alongside more focused Anglo-Saxon impressions we want to investigate trading links across the sea to places in Scandinavia and Germanic Europe, with a focus on the market town of Hedeby. These two areas of interest will hopefully allow us to explore different clothing styles, and items that would have been traded throughout Kent from further east.

Ingimundrs Land

Michelle Young

Most of you may not know me as I am fairly new to Regia. I joined with my husband John in 2022, though we have both been re-enacting since 1995. You may know my daughter Katy Lesbirel–Young and her husband Mike Lesbirel–Bray. We live on The Wirral Peninsular and I decided to put myself forward as Group Leader and help form the new group. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Colin Ellis–Vowles and Sudrjorvik for all the help and support whilst we have been waiting to apply for the Land Grant. Our Land Grant covers The Wirral peninsula, Chester and parts of the North Wales Coast. If you look on maps from 902, we are the Norse end of Mercia.

So now we have our geographical location pinned down, who are we hoping to portray? Well, we are going to be primarily a Hiberno Norse group. But we are open to playing Saxons, Danes and Norman’s too. The reason we are primarily Hiberno Norse is due to our name. Ingimundr was one of the Vikings expelled from Dublin in 902, according to the Welsh and Irish Annals (no mention of him in the Anglo Saxon Chronicles though, guess they didn’t want to give magic to his name).

Though at the moment we only have a few members, what we lack in quantity we more than double in enthusiasm. Many of you will have seen Katy and Mikes LH display with the herb garden, along with Declan and his wood carving.

We are looking forward to our first season as a group in 2026, and are already working on plans for our living history displays. Maybe our herb garden will get bigger? Or maybe we will increase our armoury? Watch this space. Every good wish

Suðfolc Gesìþas

Gavin Law

Sūðfolc Gesìþas was officially ratified in October this year based in lovely Suffolk. It has been challenging starting from absolute scratch but we are making meaningful progress. We saw a sudden influx of new members bringing us to a total of 7 members from our initial 3.

We now have a training ground which was more challenging to source than I initially thought. A lot of emails with no response and scouting the local area for green spaces. However I was able to attend a Parish council meeting where I made a successful case for use of Wetherden playing fields.

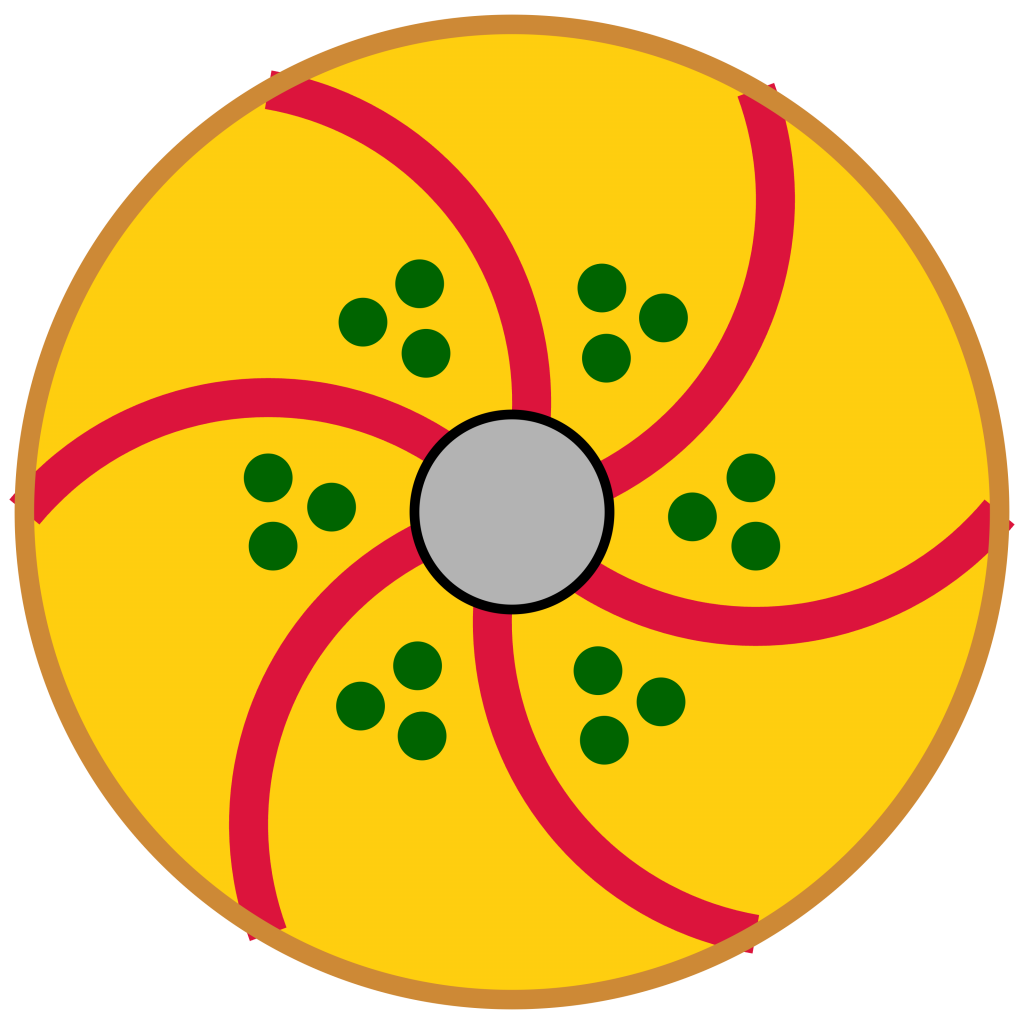

Matt Greatrex lent us his skill and designed a logo for us. We chose a Viking style horse on the colours of our group. Horses have been an integral part of Suffolk’s story from the rider found at Sutton Hoo to the modern racing scene at Newmarket and even the Ipswich football club logo.

So what’s next for the Gesìþas? In the short term I aim to have a social media account and website very soon and hopefully have some cool locals to put on the Regia calendar. My long term dream for this group and the area is to build a solid reputation and hopefully land a Regia national in Bury St Edmunds. The story of St Edmund is so integral to Regia’s core period and a real sense of identity in the city itself it would be wonderful to bring that to life and invite you crazy lot to make it happen and share in the fun.

The full list of Local Groups is on our website: Local Groups

In Your Local Area

Parchment-making and Book Arts in Furðer Strandi

John Cash

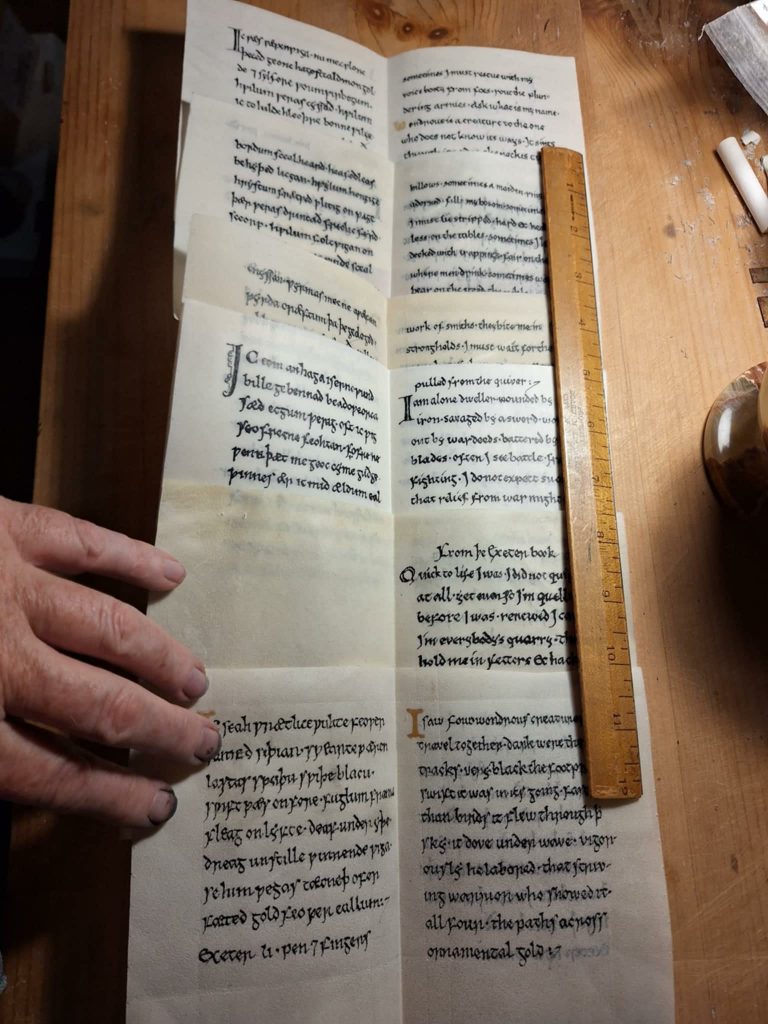

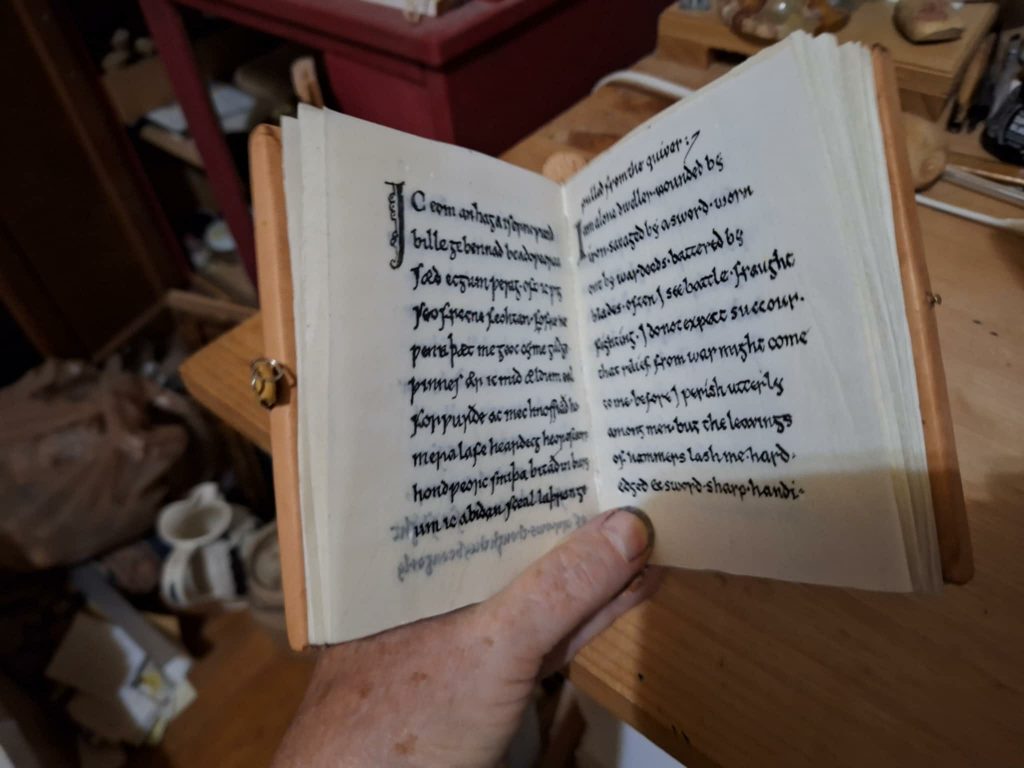

I’ve been involved in book arts for about fifty years. I began by learning calligraphy, but I became more and more interested in making my own paints and materials. Fifteen years ago I learned to make parchment, and soon I was off down the road of making books. After several years interpreting at living history museums, I earned a degree in library science and worked directly with books and records. When I was accepted into Furðer Strandi three years ago, representing a monk who made books seemed an obvious interpretive choice: seeking to interest the eorl in purchasing parchment and books from the monastery.

Of course, monks did not necessarily do all the work in the process of making a book, but certainly the monasteries and cathedrals were book-making centres. And it is important to show visitors a process. A black-robed monk bent over a two-meter-tall parchment frame strung tight with an animal skin, scraping it with a large curved knife – all appropriately researched – presents a process as well as an arresting picture.

Parchment is made from animal hide. The hides typically used were goat hides (in Mediterranean Europe), cow and calf hides (in northern Europe), and sheep hides. The type of animal reflects the animal husbandry of a given region. The skin is processed with an alkaline substance, usually added to water in which the dressed skin was soaked. The hair is removed during the process. After two weeks the skin is removed and washed thoroughly and is strung up on a frame or herse. Again, goat hides were strung on circular hoop-frames in southern Europe, while cow and calf skins were strung on larger square frames in the North. A lunellum – a knife with a half-moon blade – is used to scrape the skin’s surface (mine is a period reproduction). The cords tying the skin to the frame are tightened often. The combination of scraping and tightening breaks the binds between the protein fibers of the skin and leaves it thin and white.

A practical demonstration at an event can show only the final activities of scraping the hide. Even so, a scribe of the period had to finish the parchment further using pumice stones. So a hide on the herse allows the visitors to compare unfinished parchment with the finished material used in books.

If you have a books to show. Furðer Strandi often attends timeline events. In our camp we each have a spot and a thing to interpret – what a museum might call an interpretive station. After my first timeline event I realised two things. First, I had a compelling presentation about a medieval craft that led to early books, but I had nothing accurate to the time to show as the end-product. Second, our interpretations seemed, to me, to be disconnected from each other. So I asked myself, first, what sort of book might I make? and second, how could we connect our different interpretive stations?

The easy answer was to the let the book do the connecting.

Such a book shouldn’t be just blank pages. It should have content, a text that could be read to visitors and would engage them. I chose riddles for the text for three reasons. First, they’re often short and easy to write by hand, and easy to fit in a book format – and there is an example from Regia’s period: the Exeter Book. Second, they would engage visitors in games of guessing. Third, and most significantly, some of the riddles in the Exeter Book could be applied to objects around our camp, like eggs or shields. Once the riddle-game was over, a second game of hide-and-seek for the object could follow, and lead the visitors to a different interpreter.

Our Riddle Book reproduces about two dozen riddles in Old English and in Latin. Margins and text block conform to period layout practice. For practical reasons, the text in the original language is on one page and a translation is on the facing page. The scribal hand is based on the Anglo-Saxon of the Exeter Book, but has some alterations for legibility’s sake. The riddles in Old English are taken from the Exeter Book, and those in Latin are from manuscripts of our period by such authors as Eusebius, Symphosius, and Aldhelm.

During our period, book binding was undergoing a transition from the traditional Coptic binding method to the new Carolingian method. Briefly, Coptic binding used the same thread that bound the pages into a group to bind each group to the one below it in a chain-stitch; while the Carolingian method bound them by tying that thread to a set of heavier cords positioned along the book’s spine. Our Riddle Book has a leather cover over its hand-cut oak boards, but enough elements of the Carolingian binding can be seen inside, on the backs of the covers, that I can compare it with Coptic binding in another book, which is in preparation (and which, in keeping with many Coptic-bound books, will not have a leather cover for its boards).

The idea is to lead the visitors to an understanding that all books in our period were not just handiwork but work. They were made bit by bit, in slow, labor-intensive processes. Before the electronic age, all knowledge and spiritual wisdom rested on people doing this work. And monks were at the forefront.

I have interpreted parchment-making once each year at the time-line event in which Furðer Strandi takes part. Each year I try to return with a better kit and reproductions of more proper tools (such as those found at Portmahomack) with which to focus on parchment-making. I have learned that, while I must let the interpretation go where the visitors will, use of the Riddle Book can eclipse the parchment-making, even though riddles don’t seem to be popular with visitors here in the States (though guessing games are). Nor do I see the higher interaction between interpretive “stations” as a result.

But the eorl has asked me for a book in which he can show his lineage and worldly assets to visitors. So there’s a box checked.

Resources:

Carver, Martin, and Cecily Spall. “Excavating a parchmenerie : archaeological correlates of making parchment at the Pictish monastery at Portmahomack, Easter Ross.” Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 134 (2004), 183-200.

Exeter Dean and Chapter Manuscript 3501 (The Exeter Book)

Members Handbook. Church. Regia Anglorum, 2007 (updated 2025). Reed, Ronald. The Nature and Making of Parchment. Leeds: Elmete Press, 1975.

Szirmai, J. A. The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding. London, New York: Routledge, 1999.

Wessex Local Show – WARAG, 2025

Ian Morgan

Wessex had fun in May this year attending ‘WARAG’, which is a largely WW2 show that has been successful in the West Country for several years and is now looking to expand from it’s khaki origins and add a few flashes of colour from other periods. Camped opposite from US Cavalry from the Plains Wars & next to some holes we suspected might shelter the Viet Cong we enjoyed a very positive reaction from the public, who seemed pleased to see something completely different at their show! We also had a great ringside seat for the afternoon battle reenactment and weapons demonstrations – and who doesn’t love to see a Sherman tank in action?

In 2026 Wessex are keen to bring more members and invite people from our neighbouring groups so that we can put on a more impressive LHE & expand our combat demonstrations. The show is on the 23rd-24th May. If you’re interested, get in touch with us.

Your Research

Colouring a Saint

Alison Offer

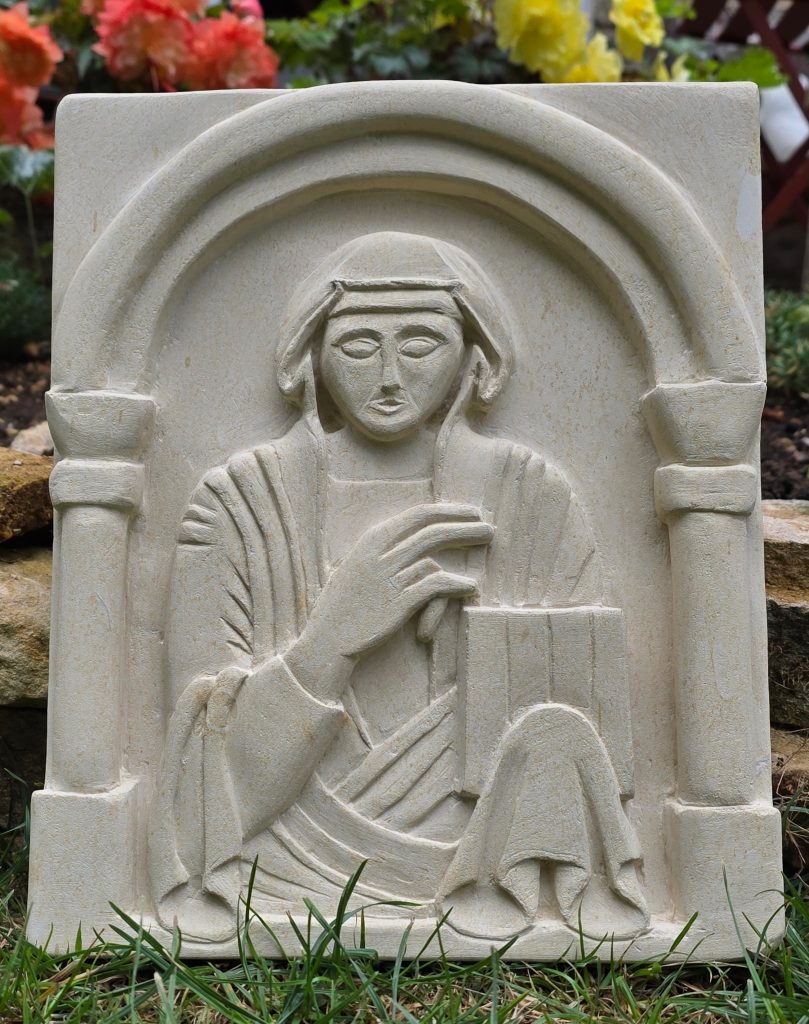

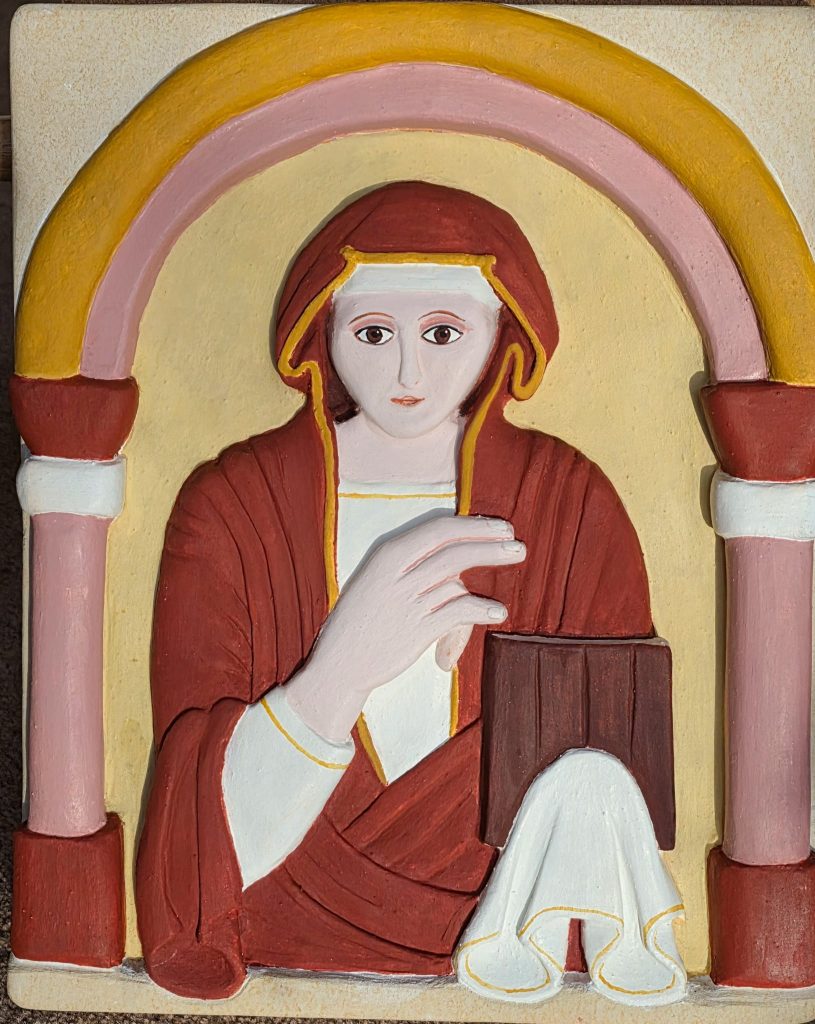

One of my favourite things is finding Anglo-Saxon sculptures tucked away in corners of post-Conquest churches: grey, weathered relics of lost Anglo Saxon minsters. The Founding Abbess is my attempt to imagine how they once of looked.

My abbess is based on the Breedon Virgin at St Mary and St Hardulph’s Church, Breedon-on-the-Hill. The Breedon Virgin is a relief sculpture about 60cm tall, dated to the late eighth or mid-ninth century and widely believed to represent St Mary. Much could be said about its iconography, the influence of Byzantine art, and what it reveals about Mercian connections with the wider world, but I was interested in how the sculpture might have looked when new. My abbess is not an exact copy. She is half-sized, so the design is slightly simplified, but her pose and clothing are the same. Like the original, she is carved in limestone, though I used a softer, more porous stone.

In August I asked for advice on Regia Members Info about how best to paint her. The first suggestions were casein (milk) paint, which has many advantages: it is chemically compatible with calcareous stone, bonds well, and produces a durable, matte, breathable surface. However, although it is often assumed online that casein paint was widely used in the medieval period, I could not find any evidence in the literature for its use in early medieval Europe, and little firm evidence before modern times. While Theophilus (12th century, On Diverse Arts) and Cennini (15th century, The Craftsman’s Handbook) discuss casein-based glue, neither mentions casein paint. Oil paint is unsuitable for limestone as it prevents the stone from breathing and is chemically incompatible. Lime paint is possible, but generally gives muted colours. So what was used in period?

Fortunately, we do have some evidence from Anglo Saxon painted sculpture. The roughly contemporary sculptures at Deerhurst, which also include a Byzantine-inspired figure of Mary, have been studied in depth (Gem et al. 2008). The paints were largely iron-oxide-based reds and yellows, with carbon black and calcium carbonate white, bound with egg. Some pigments were applied directly to unprimed stone, while others were painted over a limewash ground.

The Lichfield Angel, dated to around 800, uses the same palette and egg-tempera medium, but the paint is consistently applied over a calcium carbonate substrate. Similar earth-colour schemes—red, yellow, black, and white—have been found in fragments of wall painting from Winchester and in other early medieval English contexts. Canterbury stands alone in Anglo-Saxon England in having evidence for Egyptian Blue on its walls.

My abbess belongs to a more modest minster than Canterbury so, following advice from both Caroline Nicolay (Pario Gallico) and Jorge Kelman (Guild of Saynt Luke), I used the standard palette of red and yellow ochre, black, and white, bound with egg yolk. I have dressed her in red like the Deerhurst Virgin. Before painting, I sealed the stone with multiple layers of limewash (allowing it to cure for a month), then applied many thin layers of egg tempera to build up a richly coloured, slightly satin finish. As the paint cures, this should become increasingly weather resistant.

The Breedon Virgin has drilled eye holes, and it has been suggested that these once held inclusions that would have shone in candlelight. Drilled eyes are quite common in Anglo-Saxon sculpture – the Lichfield angel also has drilled eyes – but not universal. The Deerhurst Virgin’s face is completely flat and relied entirely on paint to define her features. As my abbess is smaller than her prototype, I chose not to drill the eyes.

I am no artist, but even so, I found that the carving sprang to life once painted. The Synod of Chelsea in 816 instructed bishops to ensure that saints to whom churches were dedicated were depicted on walls, tablets, or on the altar, and the Breedon and Deerhurst Virgins may be seen in this context. They would have been a focus for prayer and a powerful symbol of a saint’s protection. We see them now as weathered ghosts, but once they would have been vivid presences.

Resources:

The Anglo Saxon Sculpture, Breedon Parish Church

Gem R., Howe E., Bryant R. 2008 The Ninth-Century Polychrome Decoration at St Mary’s Church, Deerhurst. The Antiquaries Journal 88, 109-164

Spit-Roasted Pork with Apple and Onion

Season: Winter

Social Context: Suitable for high-status feasts, celebrations and longhall gatherings

Historical Background

Pork was the most flexible and widely available meat in Anglo-Saxon England. When preserved properly after the autumn slaughter, it could be stored through the winter months and brought out for important occasions. Apples, whether fresh from storage or dried earlier in the year, and onions appear often in the archaeological record and provide a sharp-sweet balance typical of early medieval dishes. This recipe represents the kind of celebratory roast that might be found at a winter feast.

Ingredients

- 1 large joint of pork suitable for roasting

- 12 to 18 spring onions

- 2 sour cooking apples (Grenadier, Bramley, James Grieve, Discovery)

or 6 to 8 crab apples for a sharper and more historically plausible flavour - A little honey

- A small amount of mint or dill

- A splash of sharp apple liquid or soured ale

- Salt, used sparingly

Method (Period Plausible)

- Secure the pork on a spit and begin roasting it slowly over steady coals. Turn the spit regularly.

- Combine the chopped onions and apple in a wooden bowl and moisten with honey and a little apple liquid.

- Add herbs and a pinch of salt.

- Spoon the mixture over the joint as it roasts, allowing the juices to baste the meat.

- Continue roasting until tender and cooked through.

- Serve with the softened onion and apple mixture.

Modern Kitchen Adaptation

Roast the pork in a conventional oven, basting it regularly with the apple and onion mixture. Use cider or a little vinegar for acidity, and roast at a moderate temperature until the joint is tender.

The feast does not end with savoury offerings alone. Anglo-Saxon festive meals included simple sweets made from dried fruits, grains and honey. One such dish, which suits the cold depth of winter and relies entirely on authentic ingredients, makes an excellent conclusion to the Twelfth Night meal.

Autumn Wheat Pudding with Honey and Dried Sloes

Season: Autumn and Winter

Social Context: Festive sweet dish for gatherings and longhall feasts

Historical Background

Wheat was prized for finer festive dishes. Honey was the primary sweetener of the period, and dried sloes provided a sharp depth of flavour typical of stored winter fruits.

Ingredients

- A handful of wheat grains, soaked overnight

- A little honey

- A handful of dried sloes (with stone removed)

- Fresh water or thin ale

- A pinch of mint or ground mustard seed (optional but historically plausible)

Method (Period Plausible)

- Simmer the soaked wheat until the grains soften and thicken.

- Add dried sloes and continue cooking until they plump.

- Stir in honey to sweeten and add herbs if desired.

- Serve warm in wooden bowls.

Modern Kitchen Adaptation

Use pearl wheat or cracked wheat for faster cooking. Add the dried sloes earlier for a deeper flavour and adjust honey to taste. Swap out the water or thin ale for cream for a richer texture.

Common fyrd provisions included:

- Barley or oat (for making a pottage)

- Salted or smoked pork

- Heavy-set curd Cheese

- Simple bread of barley or rye

- Foraged foods such as hazelnuts, nettles, dried apples and sloes

The Taste of Loyalty: Feasting, Fellowship and the Anglo-Saxon Fyrd

Darren Orritt

More Than a Meal

Food shaped Anglo-Saxon life in practical, social and symbolic ways. It governed the rhythm of the seasons, reflected identity and obligation, and strengthened the bonds that held households and communities together. Preparing, storing and sharing food were not simple chores. They were essential acts of survival and belonging.

In recent years I have undertaken sustained research into early medieval foodways, culminating in a detailed study titled Feasts of the Fyrd. This work draws on archaeology, manuscript sources and experimental cookery to explore how Anglo-Saxon food was prepared, preserved and shared. It highlights the significant variety of the diet and challenges the common idea that early medieval meals were bleak or monotonous.

Grinding barley on a quernstone, stirring a pot of pottage, kneading dough, brewing ale or sharing a bowl of stew were daily practices that communicated unity. These acts reinforced the strength of the household, which in turn sustained the fyrd. When we recreate similar moments in Regia Anglorum, we participate in a tradition stretching back more than a thousand years.

Food connected every member of the community, from the hlaford at the high seat to the ceorl working the infield. It also supported the fighting men called out to defend the land. Without the labour involved in farming, foraging, preserving and cooking, the fyrd could not have marched, withstood hardship or protected the kingdom. Feasting and warfare were therefore intertwined, each dependent on the other.

The Role of the Leader: Fellowship at the Hearth

In Anglo-Saxon society, the hlaford, the loaf-giver, carried responsibilities beyond warfare. He was expected to provide food, shelter and protection. The feast held in the longhall was therefore not indulgence but a central moment in which loyalty was affirmed.

The great halls of early medieval England were settings where generosity and authority were expressed through hospitality. A lord displayed his status by providing bread, roasted meats and ale, using whatever the land and season allowed. To join his table was to take part in a network of mutual obligation.

As the newly appointed leader of Grantanbrycg, I have come to appreciate this dynamic more fully. Although our responsibilities today are less formal, the principle remains. A leader creates a space where people feel valued and welcome, and shared meals play a crucial part in that. When we gather to eat as a group, we mirror the Anglo-Saxon understanding that fellowship is built through nourishment as much as training or skill.

A Year of Feasting: Twelfth Night at Wychurst

The Anglo-Saxon year revolved around the demands of the land. Spring provided new greens and milk. Summer brought peas, beans and berries. Autumn delivered the grain harvest, apples, nuts and the major livestock slaughter. Winter then arrived, a period of scarcity but also of celebration.

Twelfth Night, early in January, was one of the great winter feasts. It relied on preserved ingredients: salted or smoked pork, dried fruits, winter vegetables, pressed cheeses and grain from the previous harvest. The skill of the cook lay in transforming these dependable foods into dishes worthy of a longhall gathering.

My role in preparing the Twelfth Night Feast at Wychurst has revealed just how demanding winter cookery can be. The hall is magnificent, yet the cold slows every task. Firewood must be managed carefully, daylight is short and every dish requires constant attention. Historically plausible ingredients guide every decision. I rely on pork and beef preserved after the autumn slaughter, since these meats suit roasting and stewing and are well supported by archaeological evidence. On special occasions a household might have roasted wild boar, valued for its flavour and symbolic weight, but it was the exception rather than the rule. Winter roots such as leeks, parsnips and turnips provide substance, and herbs like mint, dill, mustard seed and parsley offer flavour supported by manuscript tradition.

Historically plausible ingredients guide every choice. I rely on pork and beef preserved after the autumn slaughter, since these meats suit roasting and stewing and appear consistently in the archaeological record. On special occasions a household might have served roasted wild boar, a prized and symbolically rich animal in early medieval culture, but one reserved for moments of celebration rather than everyday fare. Winter roots such as leeks, parsnips and turnips provide substance, while herbs like mint, dill, mustard seed and parsley offer flavour supported by manuscript sources.

At this point in the preparations I often bring forward a centrepiece dish that truly represents the character of Anglo-Saxon cookery. Two such dishes, developed during my research for Feasts of the Fyrd, have become personal favourites for demonstrating the flavours of an Anglo-Saxon winter meal. The recipes can be found to the right here. These dishes, when prepared in the Wychurst hall amid firelight and the sound of conversation, create a powerful connection with the past. The feast becomes not merely a meal but a shared moment rooted in tradition, season and community.

Sustenance for the Fyrd

Barley and oats were central. A pottage, or briw, of grains and pulses could be cooked quickly over a campfire. Wild greens such as nettles, sorrel and watercress could be gathered along the way. Small amounts of preserved pork or local fish might be added when available.

The fyrd relied on the productive strength of the household. Every fyrdman marched with food produced by family labour, drawn from the same stores that sustained everyday life. This connection between domestic preparation and military readiness is often overlooked, yet it was essential. Anglo-Saxon warfare required endurance, and endurance required nourishment. It is easy for a re-enactor to forget this at a show, where weapons and drill often take centre stage. Yet our portrayal is incomplete without demonstrating the simple, practical foods that supported a fyrdman on campaign.

Bringing the Past to the Present

From the winter warmth of Wychurst to a humble campfire at a summer show, food remains central to our recreation of early medieval life. It offers the clearest, most immediate connection between past and present. It binds us together just as it bound our Anglo-Saxon predecessors.

Every loaf shared at a Regia event, every pot stirred, every joint roasted or vegetable chopped reflects a thousand years of tradition. It affirms fellowship. It deepens understanding. It strengthens our groups and makes the living history we present richer, more authentic and more meaningful.

Seeing my daughter take part in these shared meals is a reminder of how traditions are passed forward. She is learning the pathways that connect craft, food, story and community. In doing so, she is joining a chain of continuity that stretches back to the very culture we portray.Through our feasts and our simple camp meals, we preserve the Anglo-Saxon belief that food sustains not only the body but the bonds of fellowship. The fyrd fought for its community. The household fed the fyrd. Today, when we gather and share food, we honour both.

The Artefacts and Archaeology of Jewish England

Jen Cresswell

Forgive a trip down memory lane, but I promise it is relevant. When I was at university studying archaeology, there was the question of what is an artefact? My lecturer defines it as ‘if you can kick it, it’s an artefact.’ While I’m sure some people in this very group, let alone the wider archaeological community, would disagree, or be aghast, at this as a definition, it does raise a good question on how things are defined. And when it comes to Anglo-Jewish medieval archaeology, there is the other layer of how do we define an artefact or a site as Jewish. Is it only for things used specifically in Jewish practices, like synagogues or weddings rings displaying temples, or normal everyday items like bowls that were used by people who happened to be Jewish. Is a building Jewish because it was used for Jewish purposes, or because it was used by Jewish people, or because the original builder was Jewish? What a beautiful conundrum we have managed to find ourselves in.

Identifying Jewish sites can be difficult. While names can help, this is not always so. Jewry Street in Winchester is named for where Jews lived before the expulsion, but Jewry Wall in Leicester has no association to Judaism, and a main theory is that its from the word Jury and was where local corporations met, as juries, to discuss business. As for Jew’s House in Lincoln, tradition associates it with the Jewish community, but we are not sure. A house is a house after all, and many Jewish houses at the time were indistinguishable from any other home. As such they are hard to identify.

Only one of these buildings pictured has proven Jewish links.

The almost invisibility of Jewish buildings also makes them hard to identify as specifically Jewish in archaeology. Using documents, we can make educated guesses, but by the very nature of Mediaeval Anglo-Jewish lives, many of these buildings were deliberately hidden; synagogues were often hidden behind main buildings, and we know of their use of synagogues from legal records. Or they were underground, such as the synagogue in Guildford or the Jewish scuolas or yeshivas in Nottingham and Oxford that were in crypts under other buildings. A crypt itself does not denote a Jewish use as they had more secular uses.

So we have to look at artefacts (kickable or otherwise) to help. Some, like the 13th century Bodleian Bowl from Colchester, are clearly Jewish by the Hebrew inscription which refers to members of Colchester’s community as is believed to have been given by Joseph to the community as thanks for their raising of funds to pay for his and his father’s trip to Jerusalem. Incidentally the bowl was found in the seventeenth century in a disused moat in Norfolk. Its use went from Jewish to secular, as it was reported coins were found inside so was being used as a container.

Inscription reads “This is the gift of Joseph, the son of the Holy Rabbi Jehiel – may the memory of the righteous holy be for a blessing – who answered and asked the congregation as he desired in order to behold the face of Ariel.”

Other items look, for all intents and purposes, non Jewish. But analysis indicates a Jewish use. Earthenware vases from Jewish areas show under analysis that kosher was kept as the fat residues indicate meat and diary were never cooked in the same vessel. Likewise middens show no pig bones, but high numbers of chicken and goose (three quarters of the bones were poultry from the Oxford dig, well above the national average for the period). Two bowls, one overtly Jewish, the other only under examination. Does this mean that there are more Jewish artefacts in museums that we are unaware hint at Jewish communities and use? I remember visiting the Jewish Museum in London and being saddened by their tiny display of medieval Jewish artefacts, all 7 of them in one case. But these were the ones that were explicitly Jewish. Most items people used, spoons, pins, everyday stuff, would be indistinguishable.

It all boils down to how we want to define something as Jewish. And its complicated as the Jewish community of Mediaeval England, like every community and person of the time, just wanted to live their lives. The items they used were the same as everyone else, and only very few things and places were marked as distinctly or uniquely Jewish. The vast majority were no different from everyone else. Analysis, context and research can help identify if items and places were specifically for Jewish use, but that use could also change from Jewish to Christian to secular, especially after the exclusion of 1290 were property and items were confiscated.

I don’t really have a conclusion, certainly not a definitive, grand, slightly academic sounding one; and I think that is ok. I guess, really, that my conclusion is that its complicated; but then again, history always is, and that’s the joy of it.

Questions from MoPs

We all have a series of questions that we get asked as we do our displays, and our go-to responses. What 5 questions do you know how to answer?

Board Games

Adam and Jessica Moss

“What am I looking at – are they games?”

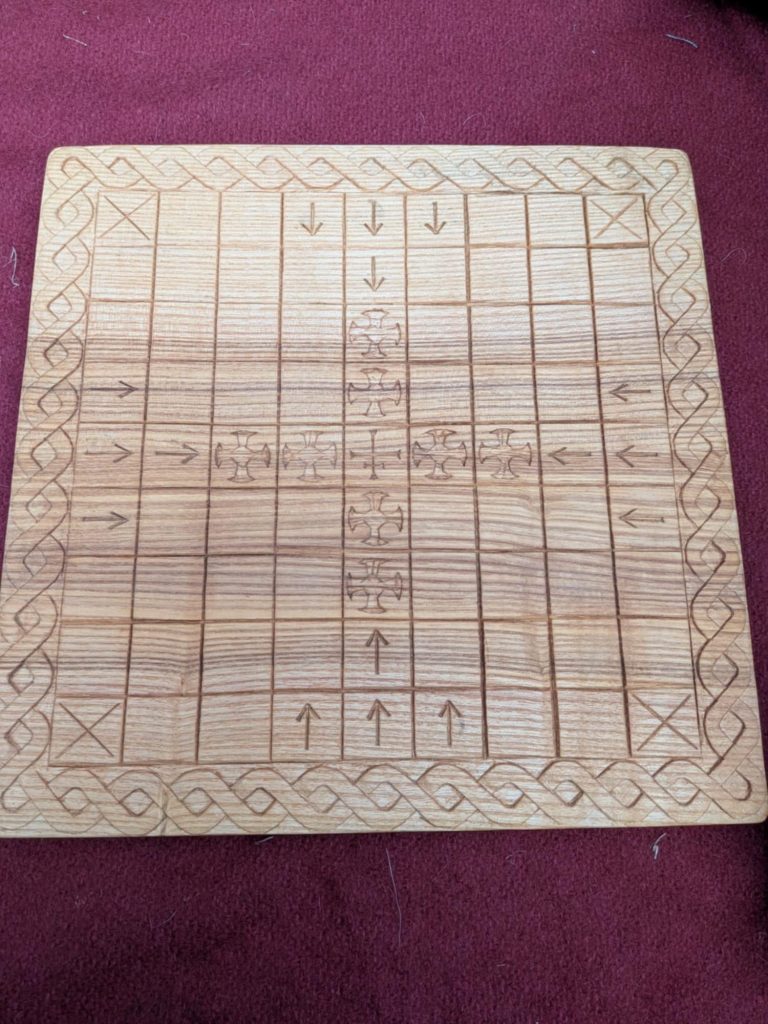

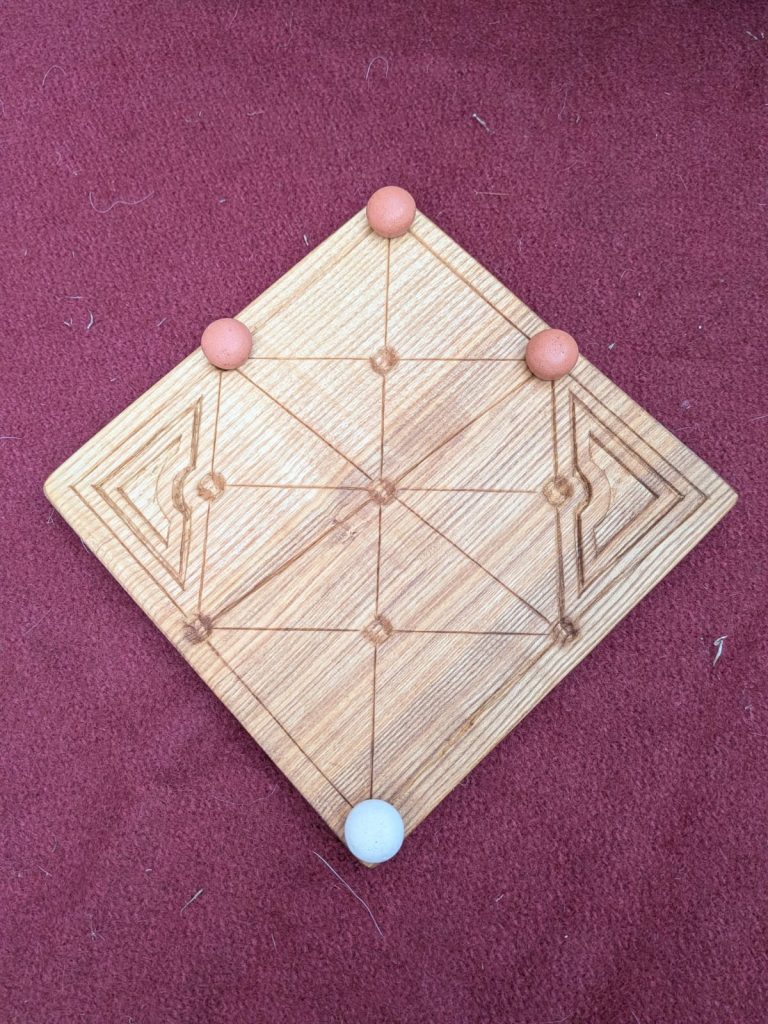

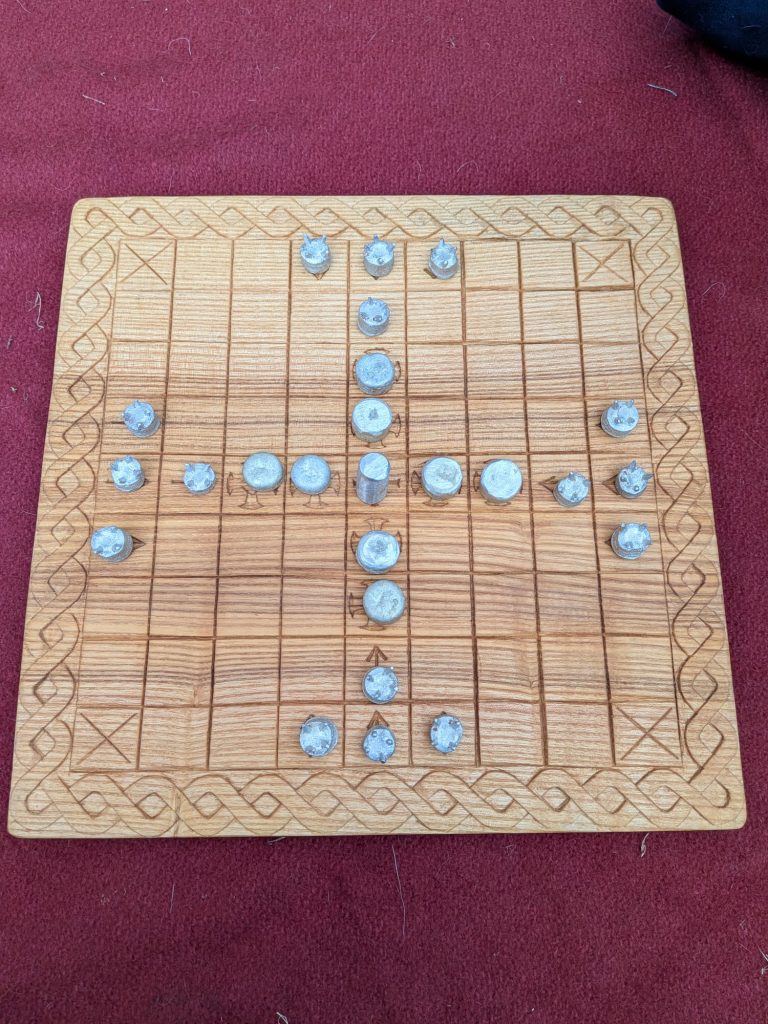

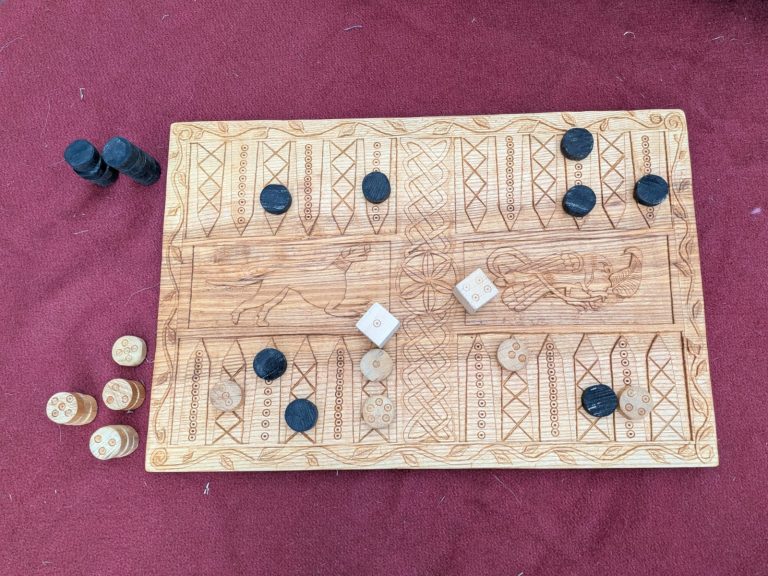

Correct! The Anglo Saxons and Vikings both loved to pass the time playing games. Just as you and your children might lose hours to an Xbox or PlayStation or PC, back in the day they would have done the same though with board games, of varying quality, amongst other, non-board games. The games you are looking at here are ‘Hare & Hounds’, Nine Men’s Morris, Hnefatafl and Tabula.

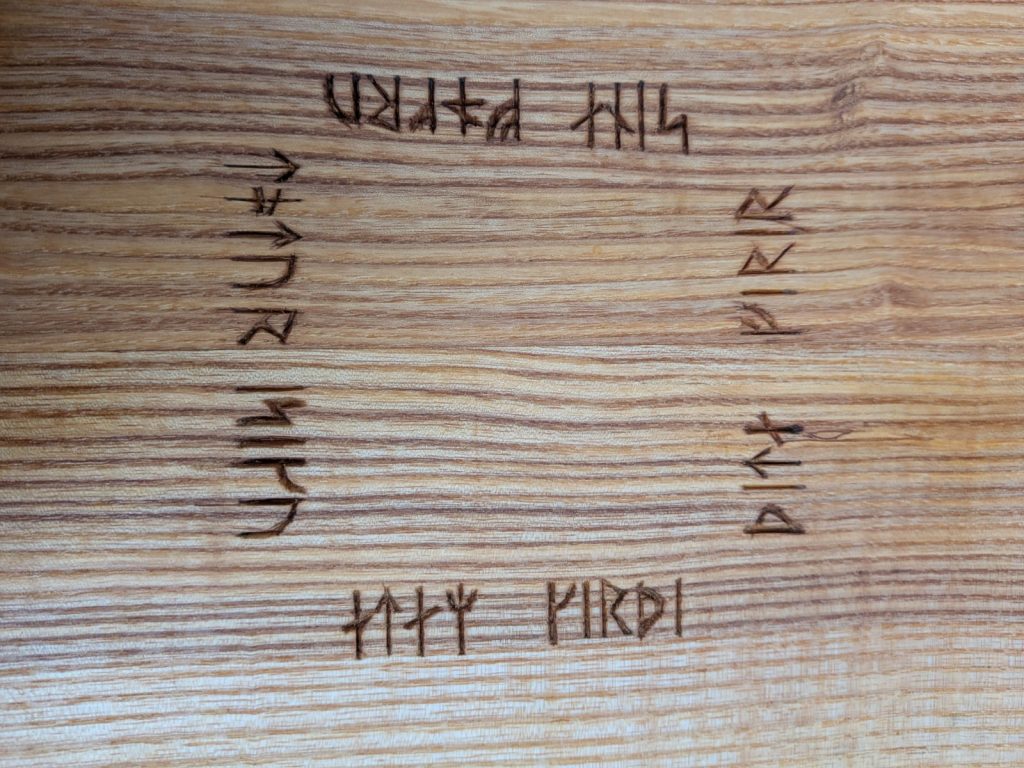

“How did you make them?”

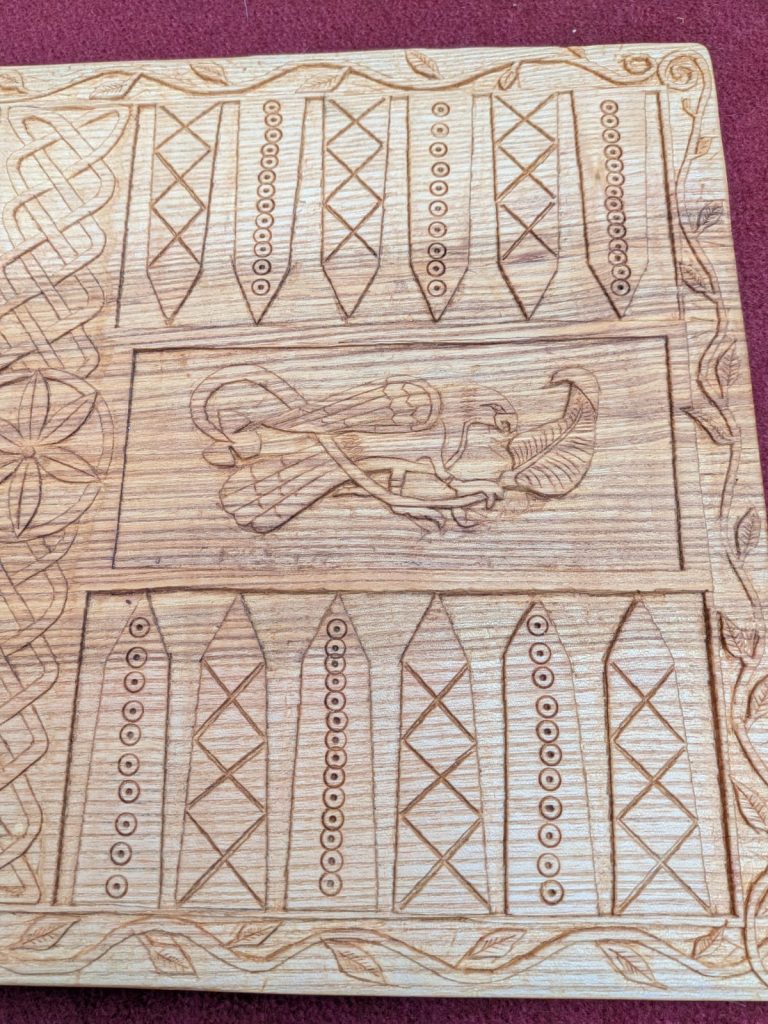

I (Adam) was keen to recreate these as authentically as I could, so I literally carved these just with a carving knife and chisel, with one modern cheat – a modified drill bit for the ring-and-dot decoration on the Tabula board. I’d not carved anything before, so the first couple of boards (Hare & Hound and Nine Men’s Morris) are simplistic without much, if any decoration. As I taught myself different techniques I felt more confident to tackle some simple decoration (Hnefatafl board) in the form of a Celtic knot border and some period-accurate runes/symbols – there’s the underside writing which reads ‘Adam made this for his beautiful daughter Jessica’ in Younger Futhark, the rune Tiwaz to denote an attacking square, a Saxon cross find I’ve used to denote a defender square and finally the reverse of a Saxon coin to denote the King square. Finally, I was arrogant/confident enough to take on the Gloucester Tabula board, well, be inspired by it to create my own version with my own researched imagery. You’ll note my group’s logo – the Saltwic Parrot on the one side, a dog from the Bayeux Tapestry that bears closest resemblance to my dog Luna, some decoration from a Saxon church font in the centre and standard vine and Celtic knot again though using three stands in lieu of two. All the boards were then treated with Linseed oil to preserve them. The gaming pieces were and are a work in progress. The Hare & Hounds/Nine Men’s Morris pieces are clay, though were bought. They will sub in until I make

some small wooden spheres as pieces. The Hnefatafl pieces have been sand casted by me and are my first ‘draft’ if you like; when my skill improves, I’ll melt them down and recreate them. The Tabula board pieces are simply cut up rounded wood to make discs. I intend to carve some more fancy pieces or cast something more impressive when I’m more skilled.

“Would they really have had boards like these?”

I (Adam) believe the boards in this form, to this detail, would be a luxury. From my limited research most game ‘boards’ would simply be scratched into wood/rocks/ship planks or even into the back of shields. There are finds such as the Ballinderry board, which is a Hnefatafl board found in, would-you-believe-it – Ballinderry (what are the odds of finding the board in the place it was named after?), with a modification of holes in lieu of board markers. This could mean it was intended to be used on ships, so the pieces remain in place when the ship is jostled around by waves. There’s also the Gloucester Tabula board which I used as inspiration – the wood has deteriorated, but the bone facade has remained.

“Were these games around before chess?”

Yes. Though Hnefatafl is known as Viking Chess, it has nothing to do with that game at all besides vaguely resembling it. Nine Men’s Morris is at least as old as the Roman Empire. Hare & Hounds/Fox & Hounds is difficult to pinpoint, in that it is a game popularised in the mid-19th Century, but by many accounts is based on earlier games which predate the Early Medieval period, but a date isn’t available. Tabula is literally a Roman game. Hnefatafl is a well-documented ‘viking’ game which spread to Anglo Saxons also. Chess has its origins in India and didn’t arrive until at least the 10th century in Spain, from there slowly making its way to England sometime around the 11th century.

“How do you play?”

Take a seat…

It’s obviously difficult to demonstrate how to play here without the boards, but in brief…! Hare & Hounds is a strategic entrapment game, where the three hounds must trap the single hare. It is surprisingly more strategic than you’d think! Nine Men’s Morris plays much like Noughts & Crosses whereby each time you make a ‘Mill’ (three in a row) you remove an opposing piece until one side is left with two pieces. Tabula is the precursor to Backgammon though takes significantly longer to play. Hnefatafl is another entrapment game where one side attempts to kill/capture the king while the other defends and helps the king escape.

Next time you see us with out board games challenge us to teach you!

Media Projects

Press and Publicity Officer

Jenn Robinson

#RegiaAnglorum

Immersive Weekends/ Feast Photos: The immersive events are amazing for photos. Not having public or ropes does allow for excellent photos that do well on socials.

Photobooth: Now has poles and can be used at any show. We find it needs to be monitored, and public encouraged to use it, so we may look into signage to make that clearer.

Access to Photos: There is now a Regia Google Drive so that images may be shared with the Webmaster and others who need them.

Photo Projects: The smoke bomb photoshoot was a great success; those images are some of my favourite ones I’ve taken! I would love to get more battlefield images like this, no ropes and in a cool context. Many thanks to those who came after hours to join in!

Web pages

Our website is full of research and society information. You can find local groups attendance for each event by visiting our Past Events page and clicking on “Attendees”.

Social Outreach

Our top posts this year:

He’s still dancing.

40.6K Views

762 Interactions

Where float the flags of unflinching men? Let not the liege’s life be taken. The Valkyries award the word of battle. -Njal’s Saga

36.9K Views

753 Interactions

There’s really no such thing as an off-season anymore.

65.7K Views

667 Interactions

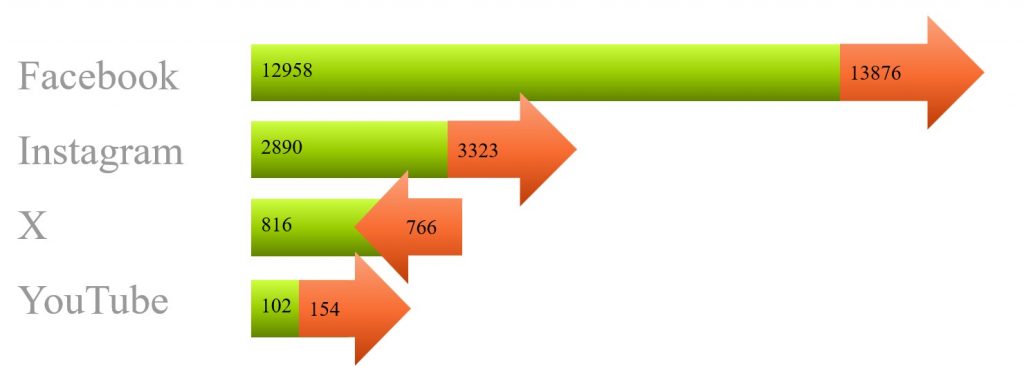

Social Media Following

We are showing consistent growth over most of the platforms and people regularly interact with our posts. Our Twitter following has gone down, but I don’t see that as a platform that suits our brand. Most posts that are posted on FB are also posted automatically to Instagram.

3 Days. 28 Degrees. Hours of fighting- often in full mail and helmets. We’re having fun… honest.

37.5K Views

475 Interactions

Website

Our website had 64024 visits in 2025. This fantastic resource is full of information about our events, officers and kit guides. There are also lots of great images and videos to show off as well.